Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

Last Updated on: 17th March 2025, 12:07 pm

Conventional geothermal electrical generation, where conditions are right, is an excellent form of renewable generation. It keeps chugging along day and night, offering firmed power with some of the highest capacity factors in the business and very low emissions per MWh. Yet, despite its many advantages, geothermal often gets left out of the clean energy conversation. Let’s dig into this a bit.

As a note, this is one in a series of articles on geothermal. The scope of the series is outlined in the introductory piece. If your interest area or concern isn’t reflected in the introductory piece, please leave a comment.

Geothermal power plants don’t rely on burning fuel. Instead, they tap into the Earth’s natural heat to generate steam, which then spins a turbine to produce electricity. Simple in theory, but not all geothermal plants are created equal.

The most common design is the flash steam plant, which pulls up high-pressure hot water from underground reservoirs. As the pressure drops, some of the water “flashes” into steam, which is then routed through a turbine to generate electricity. If there’s still enough heat left after the first flash, the remaining water can be flashed again in a double-flash system, squeezing out even more energy. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, flash steam plants account for the majority of geothermal power production worldwide.

A simpler but less common alternative is the dry steam plant, which, as the name suggests, pulls pure steam directly from underground reservoirs and channels it into a turbine. These only work in a handful of locations, such as California’s famed Geysers field, the largest geothermal complex in the world.

While binary cycle plants also exist, using secondary working fluids with low boiling points, they fall into the category of “enhanced” geothermal, which we’re leaving out of this discussion.

The average geothermal plant runs at an 80–90% capacity factor, meaning it produces power almost continuously. Natural gas plants typically hover around 50%, and coal plants, once the workhorses of baseload power, are struggling to stay above 40%.

For all the hand-wringing about “grid reliability” in the transition to renewables, geothermal already provides clean, always-on electricity. In fact, per the U.S. Energy Information Administration, geothermal plants in the U.S. often operate at over 90% capacity factor, making them some of the most consistently dependable energy sources available.

Despite its potential, geothermal remains a niche player. As of 2022, the world had around 16.3 gigawatts (GW) of installed geothermal capacity, per the Earth Policy Institute. That’s less than 1% of total global electricity capacity — a drop in the bucket compared to wind (~900 GW) and solar (~1,000 GW).

However, some countries are punching above their weight.

The United States remains the global leader, with 3,676 MW of installed capacity. California and Nevada host the largest number of plants, with The Geysers alone producing about 1,500 MW.

Indonesia is another geothermal powerhouse, boasting 2,133 MW of installed capacity. Sitting atop the Pacific “Ring of Fire,” the country has vast untapped geothermal potential, estimated at nearly 30 GW, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency. In the Philippines, geothermal energy contributes between 10–15% of the country’s electricity supply, making it one of the earliest adopters of the technology. The nation has developed 1,918 MW of installed geothermal capacity.

Turkey has experienced the fastest geothermal expansion in the last decade, growing from just 30 MW in 2008 to over 1.5 GW today, reaching 1,526 MW of installed capacity. Meanwhile, New Zealand relies on geothermal energy for about 15% of its electricity, with an installed capacity of 1,005 MW.

Other notable producers include Mexico (963 MW), Italy (944 MW), Kenya (861 MW), Iceland (755 MW), and Japan (601 MW), according to the Global Geothermal Alliance. Yes, while Iceland is famous for its geothermal, it’s actually not that big a resource compared to other countries. Of course, as its population is under 400,000, not counting the elves, demand isn’t that high either.

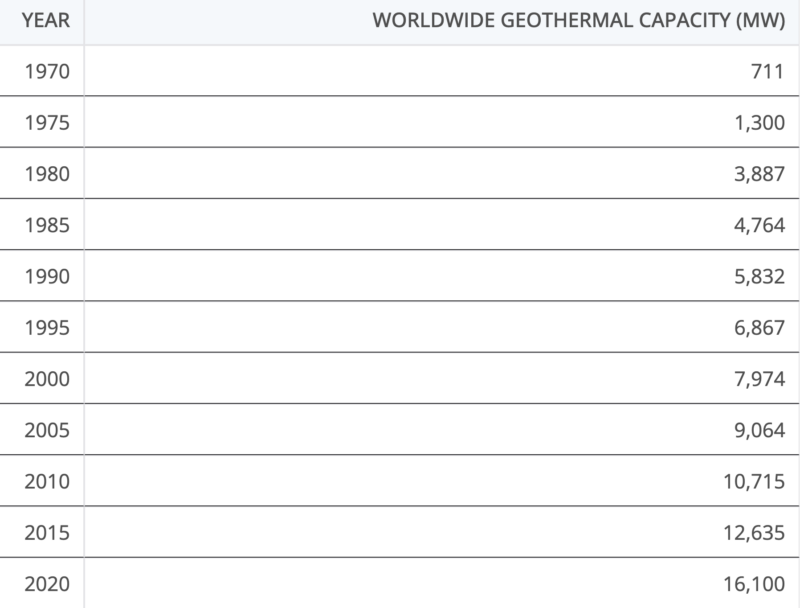

Geothermal power has been expanding steadily, but slowly. Here’s how global installed capacity has evolved:

Notice the relatively slow growth? In the 1970s and 1980s, geothermal capacity nearly quadrupled. Since then, it’s been a steady crawl instead of a boom. This isn’t entirely due to lack of potential, it’s also a matter of investment and policy support. As an example of this, British Columbia has an estimated 6.6 GW of conventional geothermal potential yet no geothermal plants in operation. As I always like to say about the province, when the discussion turns to electricity, the first, second, and third questions are Where are we going to build the dam?

Japan is another head-scratcher. It has vast geothermal potential, estimated at over 23 GW, but its development has been hindered by deep cultural and economic ties to onsen (hot spring) tourism. Many of Japan’s most promising geothermal resources lie beneath or near established onsen areas, where operators and local communities fear that tapping into underground reservoirs could deplete or alter the prized mineral-rich waters. Resistance from the onsen industry, combined with strict environmental regulations and bureaucratic hurdles, has significantly slowed geothermal expansion. Despite government incentives, opposition from powerful onsen associations continues to be a major roadblock to unlocking Japan’s geothermal energy potential. As a result, only 0.6 GW of geothermal is in operation.

A glaring absence from this geographical survey is China, which usually leads the list on everything by a large margin. However, China’s conventional geothermal resources are mostly in the far west in the Himalayas, while its electricity demand is in the south and east. Even then, estimated resource is only about 7.1 GW, barely more than BC and fraction of Japan. As a result, there’s only about 50 MW of capacity in operation.

Geothermal is a clean energy source, but it’s not impact-free. The biggest concern? CO₂ and gas emissions from underground reservoirs. Unlike wind and solar, which emit nothing during operation, geothermal can release naturally occurring CO₂, methane, and hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) trapped in deep rock formations.

On average, conventional geothermal plants emit about 45 grams of CO₂ per kilowatt-hour (gCO₂/kWh), per the International Energy Agency. That’s 20 times lower than coal (~900 gCO₂/kWh) but still higher than wind or nuclear. It’s well within the range of low-carbon generation technologies, however its lifecycle emissions aren’t going to be cut by decarbonization of extraction, manufacturing and supply chains, as is already occurring for wind and solar. What we will consider low-carbon in the future will be lower carbon than today, so it will be interesting to see if 45 gCO₂/kWh makes the grade. It’s likely that carbon capture and reinjection might start to be required in the future.

Some geothermal fields have high hydrogen sulfide concentrations, which smells like rotten eggs and, at high levels, can be toxic. Thankfully, modern abatement technologies like those at The Geysers remove 99% of H₂S emissions before they reach the atmosphere.

Flash steam plants use 1.6–2.8 gallons per kWh, which is much lower than a coal plant but higher than a wind turbine or solar panel, which uses zero water in operation.

Extracting large amounts of fluid can cause minor land sinking, though this is mitigated with reinjection. Unlike enhanced geothermal, conventional geothermal has a low risk of triggering earthquakes.

If geothermal is so great, why isn’t it growing faster? The first challenge is location dependence. Unlike wind and solar, which can be deployed almost anywhere, conventional geothermal requires high-temperature reservoirs, usually near tectonic plate boundaries. This geographic limitation means that only certain regions have viable resources for development.

Another significant barrier is the high upfront cost. While geothermal plants are inexpensive to operate, drilling wells and constructing the necessary infrastructure require substantial initial investment. Wells alone can cost anywhere from $5 to $10 million, and there’s always the risk that a well might come up dry, adding financial uncertainty to projects. As a large conventional geothermal power plant typically requires 20 to 60 wells depending on the resource temperature, permeability, and plant capacity, that adds up quickly.

Development timelines further slow geothermal expansion. Bringing a plant online typically takes between five and seven years, due to lengthy permitting processes, extensive site exploration, and the technical challenges of drilling deep into the Earth. These delays make geothermal less attractive to investors looking for quicker returns compared to wind or solar projects, which can often be completed in just a couple of years.

There are two opportunities for long-tailed risks — black swans — in those last couple of paragraphs. Anything we do fiddling around under the surface of the earth has much higher potential for failures of a wide variety of types because we have mostly indirect means of knowing what’s down there. That’s why tunneling and tunneling are well into the high-risk zone of categories of megaprojects, per Bent Flyvbjerg. Not nearly as bad as nuclear or the Olympics, but still not for the faint of heart. And that time duration is important too. As Flyvbjerg points out, statistically and anecdotally, the longer a project takes, the more that external conditions might shift during execution. COVID-19 anyone? Trump 2.0 and its tariffs, anyone?

By contrast, wind, solar and transmission (and undoubtedly grid battery storage, although Flyvbjerg doesn’t yet have a category for it) are very low risk. Once the shovel hits the ground they are very likely to hit time and budget targets and deliver the projected benefits. The iron law of megaprojects, per Flyvbjerg is that only 0.5% of them achieve the trifecta of hitting schedule, budget and benefits targets, and wind and solar are much more likely to be in the 0.5%. That’s the power of modularity, manufacturability, global supply chains, and parallelization of construction.

While there are legitimate barriers to growth for conventional geothermal, the case for ramping up investment is clear. If policymakers are serious about clean, reliable energy, then conventional geothermal electrical generation should be getting a lot more love in places like BC and Japan.

Whether you have solar power or not, please complete our latest solar power survey.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy