Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

As the world races toward a decarbonized future, hydrogen is often touted as a clean energy carrier, with proponents highlighting electrolysis as a viable method for its production. The process, which uses electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen, can indeed be powered by renewable energy sources, making it seemingly emission-free. However, a closer look at the numbers reveals a sobering truth: electrolysis is an inefficient and costly detour compared to direct electrification.

This is a companion article to the Cranky Stepdad vs Hydrogen for Energy material. In a similar manner to John Cook’s Skeptical Science, the intent is a rapid and catchy debunk, a second level of detail in the Companion to Cranky Stepdad vs Hydrogen for Energy, and then a fuller article as the third level of detail.

Electrolysis for energy-carrying hydrogen is like driving in circles when the straight path is just ahead — inefficient and wasteful.

Electrolysis is often framed as a zero-emission solution, but this narrative conveniently omits a crucial factor: efficiency losses. Studies show that hydrogen production via electrolysis suffers from significant energy losses at every stage. The International Energy Agency (IEA, 2021) reports that electrolysis incurs efficiency losses of 30-50%, making it a poor substitute for direct electrification in most applications.

Bhandari, Trudewind, and Zapp (2014) conducted a lifecycle assessment of hydrogen production and concluded that electrolysis is highly energy-intensive, with the overall cleanliness of the process entirely dependent on the electricity source. Producing hydrogen via electrolysis requires approximately 50–60 kWh of electricity per kilogram, yet the resulting hydrogen delivers only about 33 kWh of usable energy, meaning that 40-50% of the energy is lost in the conversion process.

By comparison, battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) achieve an overall efficiency of around 77-90%, while hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs) operate at just 25-35% efficiency when accounting for electrolysis, compression, storage, transport, and fuel cell conversion (van Renssen, 2020).

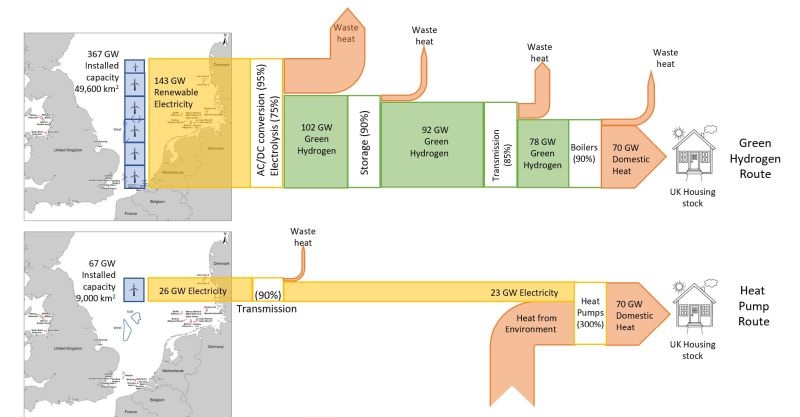

Similarly, heat pumps can deliver 3-5 times the energy they consume, making them vastly superior to hydrogen for space and water heating applications. David Cebon of the Hydrogen Science Coalition illustrates this inefficiency with a Sankey diagram comparing the energy flows of heat pumps and hydrogen-based heating (2024). His analysis shows that starting with 100 units of renewable electricity, heat pumps can deliver approximately 270 units of useful heat due to their high coefficient of performance (COP). In contrast, hydrogen-based heating, after accounting for electrolysis losses, compression, storage, transport, and final combustion, delivers only about 50 units of heat from the same 100 units of electricity. This stark difference reinforces the argument that hydrogen is an inefficient detour for heating applications, requiring over five times the energy input compared to heat pumps. In essence, every unit of electricity diverted to electrolysis results in significantly greater energy losses than direct electrification solutions.

A Costly Misstep

In addition to energy inefficiency, electrolysis is financially prohibitive. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE, 2023) acknowledges that the current cost of electrolysis is a major hurdle, with high capital and operational expenses making it unlikely to compete with battery storage or direct grid consumption of renewables.

Further, the European Federation for Transport and Environment (2021) warns that relying on electrolysis for large-scale hydrogen production would require vast amounts of renewable energy capacity. Green hydrogen’s inefficiency means that to replace just 10% of global natural gas consumption with green hydrogen, electricity demand would increase by over 5,000 TWh annually, roughly the total power generation of the European Union. Such a massive diversion of renewable resources could slow the broader energy transition by reducing the availability of clean electricity for more efficient applications like electrified transport and direct grid use.

The high costs of hydrogen have been borne out by real world deals. In 2023 in Europe hydrogen electrolysis costs were closer to €10 per kg than costs as low as €1 per kg used by early studies of hydrogen as an energy carrier. Recent projections from Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) underscore the financial challenge as well. In 2024, BNEF tripled its long-term cost estimates for green hydrogen manufacturing by 2050, citing rising capital expenditures, supply chain constraints, and slow cost declines in electrolyzer production. This revision highlights the persistent difficulty in making hydrogen economically competitive with direct electrification.

Moreover, hydrogen manufacturing costs are only part of the equation — the expenses associated with distribution, storage, and conversion further compound its inefficiencies. Due to hydrogen’s low volumetric energy density, it requires energy-intensive compression or liquefaction, and pipeline infrastructure remains prohibitively expensive in most regions. These additional costs make green hydrogen a significantly more expensive energy vector than initially anticipated.

A Detour, Not a Destination

The enthusiasm surrounding electrolysis often overlooks its fundamental inefficiencies. The reality is that for most applications, it will always be lower in emissions and cost to use electricity directly. As Temple (2021) succinctly put it in the MIT Technology Review, the hard truth about green hydrogen is that it wastes significant energy compared to direct electrification, making it an impractical option for decarbonization in most sectors.

While green hydrogen has an essential role in decarbonizing industrial processes that currently rely on fossil hydrogen — such as ammonia production, refining, and certain chemical processes — its broader use as a general energy carrier remains problematic. Electrolysis is not the clean energy breakthrough it is often portrayed to be; rather, it is an expensive and inefficient solution for applications where direct electrification provides a far superior alternative.

The path to decarbonization is clear: prioritize direct electrification where possible, and deploy green hydrogen strategically where it is truly indispensable—namely, in industrial feedstock applications that lack viable alternatives. Attempting to expand hydrogen’s role beyond these necessary niches risks wasting scarce renewable energy resources, ultimately making the energy transition more difficult and expensive.

References

- Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF). (2024). Hydrogen’s Growing Cost Challenge: Revised Long-Term Projections. London: BloombergNEF

- Bhandari, R., Trudewind, C. A., & Zapp, P. (2014). Life cycle assessment of hydrogen production via electrolysis – A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 85, 151–163.

- Cebon, D. (2024) Hydrogen vs heat pumps Sankey, LinkedIn.

- European Federation for Transport and Environment. (2021). Electrolysis for Hydrogen: A Costly Detour for the Energy Transition.

- International Energy Agency (IEA). (2021). The Future of Hydrogen: Seizing Today’s Opportunities. Paris: IEA.

- Temple, J. (2021, February 4). The hard truths about green hydrogen. MIT Technology Review.

- U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). (2023). Hydrogen Shot: Electrolysis Cost Reduction Roadmap. Washington, DC: DOE.

- van Renssen, S. (2020). The hydrogen solution? Nature Climate Change, 10(9), 799–801.

Whether you have solar power or not, please complete our latest solar power survey.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy