Sign up for daily news updates from CleanTechnica on email. Or follow us on Google News!

LNG exports are a big US success story in recent years. The first large export terminal was commissioned in 2018, and only seven years later, the country is the largest LNG exporter in the world, providing about 20% of the global supply. The industry has had a lot of favorable press as well, with many people thinking it was a climate solution (when it wasn’t).

The Biden administration paused approvals for new LNG export terminals in January 2024 due to concerns over climate impact, domestic energy prices, and long-term global demand uncertainty. The European Energy Crisis had caused global LNG prices to spike, and as the USA was exporting a lot of natural gas, the domestic energy market started reflecting international prices, leading to a lot of unhappy consumers.

In 2019, the average residential price of natural gas in the United States was $10.32 per thousand cubic feet (Mcf). In 2022, it jumped to $13.83 per Mcf and then $15.20 per Mcf in 2023. US industrial, commercial, and residential heating expenses increased by 50%, far above the rate of inflation, and that was due to LNG exports. During the peak of European demand, a single LNG shipment could clear over $200 million in profits, so LNG exporters were buying as much as they could ship, driving up domestic prices.

While the LNG industry and Republicans blamed climate hysteria and pointed fingers at Robert Howarth’s lifecycle carbon assessment as the culprits, domestic energy prices undoubtedly had a lot more to do with it. After all, most of the increase in exports occurred while Biden was President, and he was focused on trying to improve the finances of all Americans, not just the top 1%.

As a note, on Howarth’s LCA, I reviewed it and the primary critique of it that is usually shared in October of 2024, when it finally made it through one of the most arduous peer-review processes imaginable. While an imperfect LCA, Howarth was the only person asking the important questions about actual climate implications and working to understand and publish on them. His work is accurate in stating that full lifecycle emissions for extracting, processing, distributing, liquifying, shipping, and burning LNG make it a climate problem, not a climate solution.

Other academics are running scared from the entire subject. One long term contact was incredibly harsh about the Howarth LCA as they work at MIT and do LCAs professionally. They told me that they could assemble a better LCA from the component LCAs MIT maintains in a morning. I asked them why they didn’t, and the silence was deafening. I consider it ethically and morally reprehensible of academics and researchers capable of doing the LCAs refusing to and instead vociferously and publicly critiquing Howarth’s work. If they refuse to engage productively, they should shut up about Howarth’s work, in my opinion, keeping critiques solely within the academic peer review process.

One of the 220 executive orders President Trump signed on January 20, 2025 was “Unleashing American Energy,” which, among other provisions, ended the moratorium on new LNG export permits imposed by the previous administration.

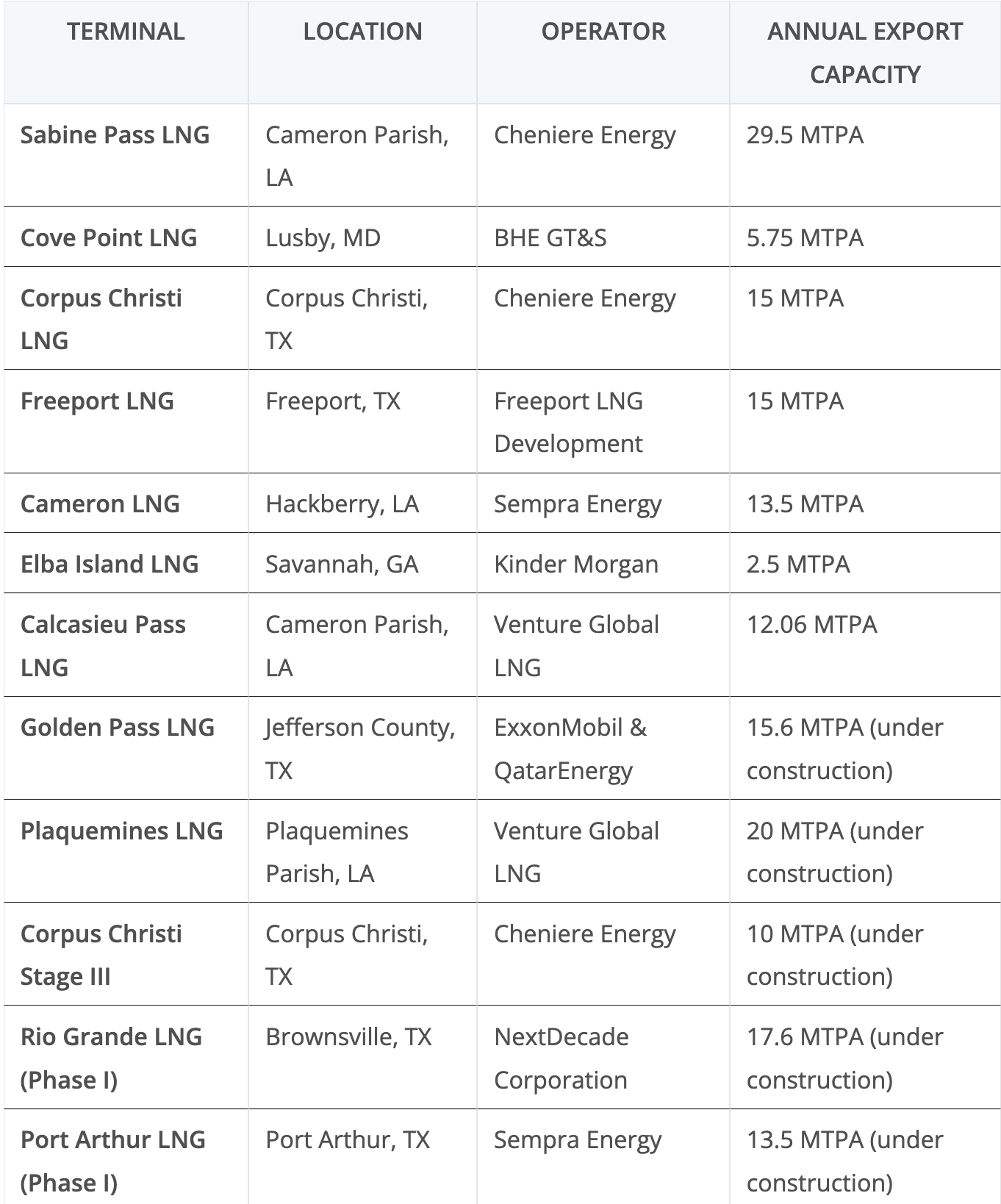

Of course, Biden’s pause didn’t stop the five terminals already in construction. The United States currently has an operational LNG export capacity of 93.31 million tonnes per annum (MTPA), with an additional 76.7 MTPA under construction. If all projects under construction are completed as planned, the total US LNG export capacity will rise to approximately 170 MTPA.

For context on 170 MTPA, the global LNG market was just over 400 MTPA in 2024, with the USA supplying about 20% of it. Almost doubling export capacity with the LNG terminals under construction presupposes a massive increase in global LNG demand and much increasing US dominance of the market.

As of the latest data, there are 17 pending applications where US businesses are seeking approval to build and operate terminals to process LNG for sales abroad. Presuming that they are in the same range as the ones under construction and get built, that suggests another 260 MTPA of capacity coming on line from 2029 to 2035, leading to a total US export capacity of 430 MTPA, more than the entire global market for LNG today.

That seems quite remarkably absurd to me. Even the current under construction capacity and much of the current operational capacity is at risk of shuttering in the 2030s. These are supposed to be 30-50 year operational assets because they cost so much to build. Large export terminals cost $15 to $25 billion and large import terminals cost up to $3 billion, with the liquification facilities in the export facilities being the expensive bits.

Global LNG trade only grew by 2.1% in 2023 and data suggests the same growth rate in 2024. This doesn’t lead to a market that will support massive growth of US exports.

This is the decade of peak fossil fuels, not massive growth of fossil fuel demand. Over the past two years, Pakistan, for example, installed 40 GW of solar, when its entire 2023 generation capacity was only 46 GW. Brazil added about 15 GW of wind and solar to its already extensive renewables fleet over the two years. Mexico, Egypt, Indonesia, and Kenya are other notable developing countries hammering in wind and solar.

Countries that do business with China globally — all of them — and especially the ones in the Belt & Road Initiative — three-quarters of them — are also buying lots of grid and behind-the-meter batteries and electric vehicles of all scales from the country. That’s just increasing. Solar and batteries are incredibly easy to install. People in developing countries can generate their own transportation fuel from sunshine, and are. That doesn’t make for a huge growth market for LNG imports.

The three big markets for LNG are Europe (30%), China (18%), and Japan (17%). But Europe is continuing to hammer in renewables and it does carbon accounting better than anyone. It knows US LNG is a fuel of last resort and that it needs to wean itself off of fossil fuels, and is doing so. European imports in 2024 declined by 20%. Japan’s imports have been dropping as well, declining 9% over 2023 and 2024.

China has been increasing its imports over the past years, but that has a short lifetime. First of all, China has about 75 MTPA of pipeline capacity already in operation from neighboring countries and another 60 MTPA of capacity in construction or planning. LNG gas is two to four times as expensive as pipeline gas even under 20-year firmed contracts, and much more when it’s competing for best price globally.

Further, the US export dominance is based on hydraulic fracturing for shale oil and natural gas. The thing about fracking is that it’s a technology, not a fuel, and technologies can be recreated or imported. That’s exactly what China is doing. The country possesses substantial shale gas resources, with estimates indicating approximately 1,115 trillion cubic feet (31 trillion cubic meters) of technically recoverable shale gas. This positions China among the countries with the largest shale gas reserves globally. While they’ve been having some challenges, in 2023, shale gas accounted for about 12% of China’s total natural gas production, providing about 19 MTPA.

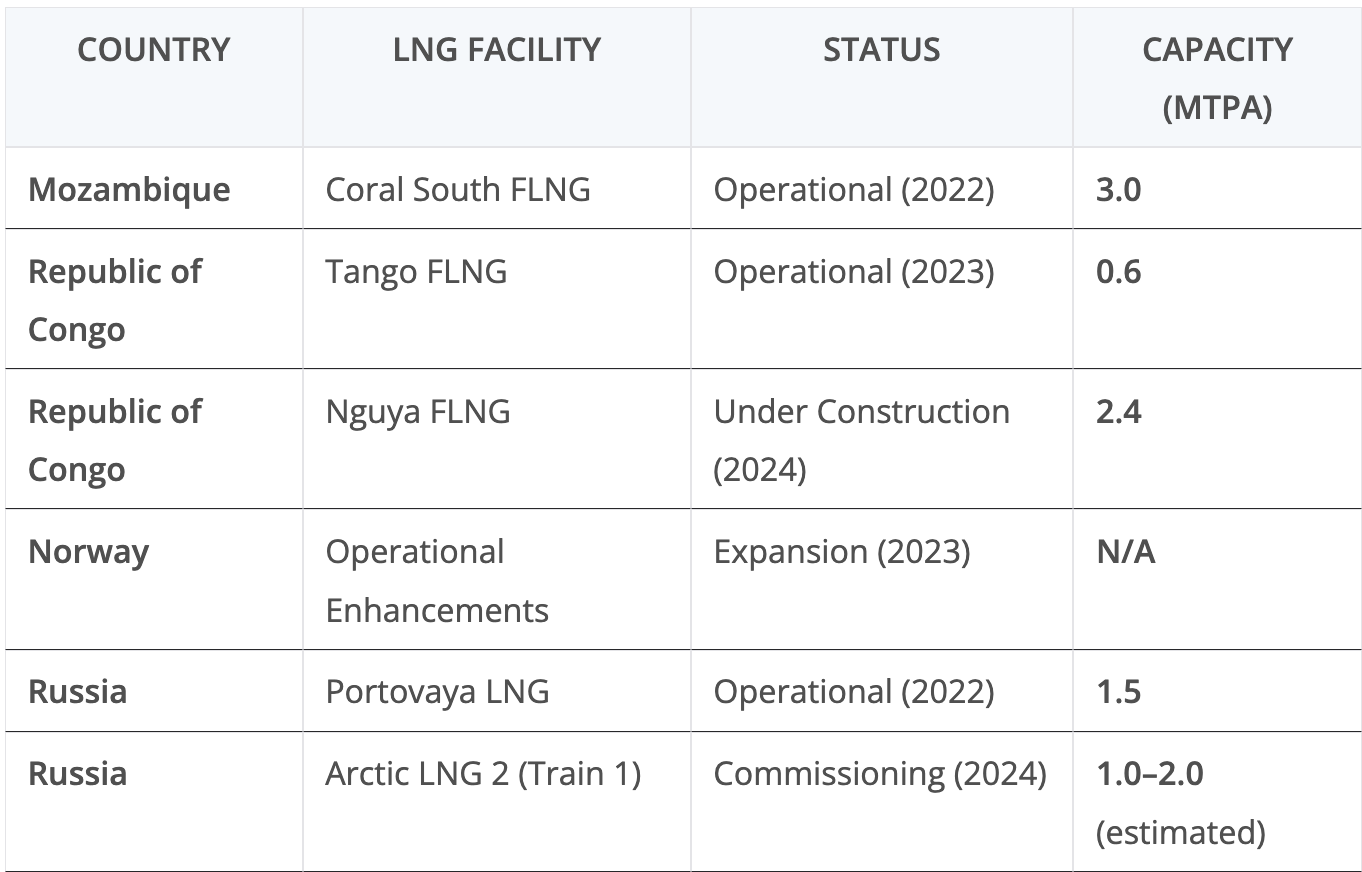

And then there are suppliers which aren’t waging a cold war of words and tariffs with China. Both Mozambique and the Republic of Congo have brought on new LNG export ports in the past three years, bringing completely new sources of supply to the market. Traditional exporters including Norway and Russia are bringing capacity up as well. It’s not like the United States is the only player on international markets or that its exports to the only major increasing market purchaser are remotely guaranteed.

On the supply side, China won’t need expensive US LNG. And then there’s the demand side. China’s natural gas demand is dominated by the industrial sector, which accounts for approximately 55% of total consumption, driven by manufacturing, chemical production, and industrial heating. The residential and commercial sector follows, making up around 26%. The electric power sector consumes roughly 16%, as natural gas-fired plants contribute to China’s energy mix, though coal remains dominant. The remaining 3% is used in transportation and other sectors, including gas-powered vehicles and miscellaneous applications.

But China is rapidly pivoting to electricity from renewables, firmed with grid storage, for all of those segments. In the past couple of years it exceeded Europe’s percentage of electrification and is the most electrified major geography in the world, while in 1990, it had a lower percentage of its energy as electricity than Europe, the United States, and India. It reached 50% of capacity in renewables in 2024, six years ahead of plan. It’s electrified industry much more than the west, with BASF’s new Shanghai plant being a case in point. It uses only electricity for process energy and as a result has only process emissions of greenhouse gases, not fossil fuel emissions. As a result, its emissions are about 15% of what an equivalent fossil fuel-powered plant would be.

Within industrial demand is one of the few bright spots for natural gas at all, which is its use as an industrial feedstock. About 7% of total demand is for that purpose, and that’s at risk of being supplanted by anthropogenic biomethane, which is a problem area we aren’t tackling nearly seriously enough. Anywhere with concentrated biological emissions of methane including centralized livestock facilities, landfills, wastewater treatment plants, agriculture manure management, and breweries and distilleries, is going to change processes to minimize them, but also be subject to methane capture. Pushing that as an industrial feedstock and into strategic energy reserves for very long duration storage makes the most sense to me.

Unsurprisingly, China is the world’s largest market for heat pumps as well as being the world’s largest manufacturer of them, and is pivoting residential heating and cooking off of fossil fuels and biomass at a great rate, in part because urban air pollution was such an enormous problem through the 2010s and into the 2015s. Residential, industrial, and commercial demand for natural gas is going to plummet.

China is hammering in grid storage, which competes directly with natural gas generation to balance renewables. It has about 365 GW of power capacity and perhaps 12 TWh of energy capacity of pumped hydro in operation, in construction or planned to start by 2030 (incidentally dwarfing their nuclear program). A single auction for 16 GWh of grid battery storage energy systems in December saw 76 submissions with an average of $66/kWh for full systems installed with 20 years of maintenance.

Of the three largest markets for LNG, in other words, two are already reducing demand and the third is about to start reducing demand. That doesn’t seem like the basis for massive investment in new US terminals and more like the existing US terminals are going to be in fiscal trouble in the early 2030s.

Then there’s the supply side in the United States. There are two big challenges on the supply side separate from the massive methane emissions. The first is that US natural gas comes from shale these days, either as a byproduct of shale oil extraction or from fracking for natural gas. A key thing that was discovered about shale oil and gas is that developed sites just don’t last that long, perhaps two to three years. Most of the potential shale oil and gas sites have been identified and are owned by different developers.

Over the past few years, there’s been a lot of consolidation of shale sites by international oil and gas majors. Each site is qualified for how much it’s going to cost to bring online and its likely output. Naturally, all of the cheapest to bring online with the highest output have already been exploited. The United States is into the middling sites that aren’t guaranteed to make a sufficient profit unless oil prices stay high.

About 78% of US natural gas these days comes from shale sites. A harder to determine percentage is the amount that comes as a byproduct of shale oil. One of the factors for shale oil site value is the ratio of oil to gas that will come out, with higher portions of oil being preferred, obviously. Perhaps 30% or 40% of natural gas in the States is from shale oil sites.

Pretty much everybody credible is projecting a reduction in crude oil prices in 2025, and that’s being seen already in January with the Brent Crude Index already off 5% and the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) projecting an average of $79. The EIA is a booster for the industry that’s lost credibility, being more like OPEC in its projections than a realistic organization. CITI, for example, is projecting an average of $67, and industry observers and long term energy traders like Gerard Reid are projecting volatility, with it hitting $40 at least once in the year. The International Energy Agency (IEA) is projecting good global supplies through 2024, so no upward price pressure.

Volatility amid generally declining crude oil prices is not a recipe for gaining investment approvals for new shale oil sites in the US. That’s why one of my predictions for 2025 was declining US crude extraction.

As more gas comes out of what poorer shale oil sites get approved, that might mean supplies continue, but it is just as likely to mean a decline in domestic supply, if not in 2025, then certainly in the coming years.

Then the LNG terminals will be paying more and more for the domestic supply, driving US domestic energy prices for residential, commercial, and industrial heating and for its big fleet of natural gas electricity generators up considerably. The combination is likely to mean closer to European costs, which were four times America’s already 50% higher prices in 2024.

Trump’s policies are going to create a domestic energy crisis for the United States, in other words, and make domestic politics even more warped. “It’s the economy, stupid,” and when everyone is paying two to four times as much for the 43% of domestic electricity that they get from natural gas, that’s a lot of voters. That percentage is higher in commercial and industrial sites, so global (and domestic) competitiveness of the USA’s companies is going to be challenged as well, and firms that have challenges passing those increased costs on to customers will be going out of business, impacting a lot more voters.

And 43% of US electricity comes from natural gas, with its primary expense being natural gas. Wholesale electricity prices typically correlate with natural gas prices, as natural gas power plants (especially combined-cycle plants) often set the marginal price in electricity markets. Historical data suggests that for every $1/MMBtu increase in natural gas prices, wholesale electricity prices rise by ~$8–$12/MWh. Doubling the cost of domestic natural gas would raise wholesale electricity prices by 30% to 50% and retail electricity prices by 10% to 30%. Tripling would double wholesale rates and cause retail rates to jump by 50%.

Trump’s executive order, “Unleashing American Energy,” should be labeled “Unleashing Energy Price Increases For Americans,” in other words. That’s going to lead to significant political backlash on top of the very clear increases in prices Americans will pay due to tariffs. Americans got what they voted for, and they are going to regret it deeply.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy