Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and/or follow us on Google News!

A traveler books a long-haul flight from Frankfurt to Singapore and notices a line item labeled “Environmental Surcharge.” It’s not optional, and it’s not tiny. For most economy passengers, it adds somewhere between €6 and €20. In business class, it can go much higher. At first glance, this might seem like a minor annoyance—another in a growing list of airline fees. But that small surcharge is the tip of a much larger shift: the full cost of aviation decarbonization is beginning to land squarely with the customer.

Sustainable aviation fuel, or SAF, is the aviation industry’s primary tool to cut lifecycle carbon emissions without fundamentally changing the airframes or propulsion systems that have defined commercial flight for decades. SAF can, in theory, slash emissions by up to 80% compared to traditional Jet A fuel. In practice, its contribution is far smaller today—less than 1% of global jet fuel use—but that share is growing rapidly, driven by policy mandates in the EU, UK, and Singapore, and increasingly by corporate net-zero travel programs. The catch is cost. SAF, whether derived from used cooking oil, forestry residues, or purpose-grown biomass, typically costs two to five times as much as fossil jet fuel. Synthetic e-fuels derived from green hydrogen are even more expensive—often eight to ten times—and face enormous scaling barriers.

According to the International Energy Agency, global SAF production was approximately 600 million liters in 2023, a twelvefold increase over 2019 levels but still a fraction of what is needed. The IEA projects that to meet net-zero aviation pathways, SAF will need to account for at least 10% of global jet fuel consumption by 2030, rising steeply thereafter. The EU’s Fit for 55 package mandates 2% SAF in 2025, 6% by 2030, and 20% by 2035 for all flights departing EU airports. Singapore will require 1% from 2026, scaling to 3–5% by 2030, and is introducing a SAF levy on tickets to fund that mandate. Airlines aren’t absorbing those costs; they’re passing them through.

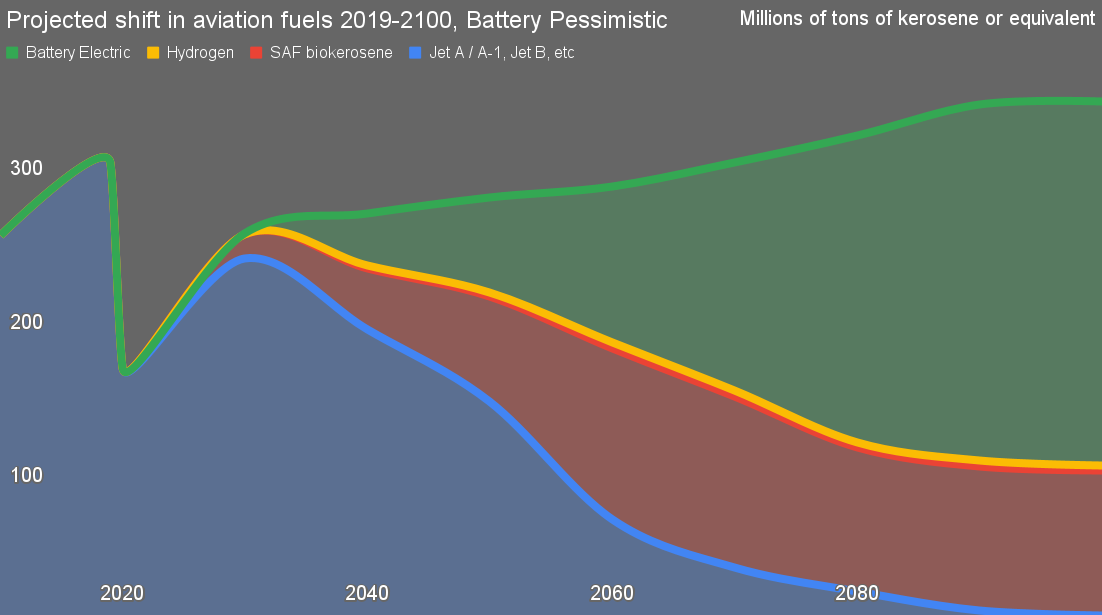

This is something that’s built into my projection of aviation demand and decarbonization through 2100. Airlines aren’t charities and climate change is real, so the industry is going to have to pay for low-carbon power, and what costs there are will be born by passengers. Most projections ignore electric aviation, but I’ve discussed this with top people at Ryanair, aerospace engineers and electric aviation founders globally. We all agree that hybrid electric aviation for up to 1,000 km routes with 100 passengers is inevitable, and that will cut a lot of flights out of the jet fuel demand equation. Further, increased flight costs will significantly soften the demand increases seen from 1980 to 2019. COVID itself fundamentally altered the industry, with significantly less business travel in the Age of Zoom. Now there’s data on how airlines are already passing costs along.

This pass-through is happening in multiple ways. In Europe, full-service airlines like Lufthansa and Air France–KLM have implemented mandatory SAF surcharges that scale by route and class. Lufthansa’s fee can reach up to €72 for long-haul business class tickets. In Singapore, the government is levying a SAF charge directly on tickets. Finnair and United Airlines offer voluntary SAF contributions during booking, typically a few euros or dollars, framed as an easy climate action. Meanwhile, corporate travel programs have emerged as SAF buyers of last resort, with firms like Microsoft, Deloitte, and Boston Consulting Group paying premiums through programs like United’s Eco-Skies Alliance and Lufthansa’s Compensaid Corporate. These arrangements use book-and-claim accounting to decouple the physical fuel uplift from the emission reduction benefit, allowing companies to claim SAF-related reductions even if the fuel was burned elsewhere.

Yet the real story isn’t just how airlines are pricing SAF today. It’s how this dynamic reshapes aviation economics in the next decade. A 10% SAF blend, which may be mandatory in some jurisdictions by 2030, could increase total fuel costs by 20–30% if the price premium holds. That’s before factoring in airport blending logistics, certification costs, and potential penalties for non-compliance. Since jet fuel historically comprises 20–30% of airline operating expenses, this is a structural cost pressure that can’t be ignored. Airlines operate on thin margins. They will not, and cannot, absorb that burden alone. Ticket prices will rise.

The industry projects rising demand in spite of this, something I think is wishful thinking. Boeing and IATA forecast that global passenger traffic will double by 2040, citing long-term economic growth and expanding middle classes. But these projections rest on historical price elasticity that may no longer hold. Airfare inflation, driven by decarbonized fuel, is likely to cap growth earlier than IATA expects. Per analysis from Transport & Environment and others, a 20% rise in average ticket prices could reduce demand by 10-15% depending on the route and travel purpose. That would be enough to flatten growth curves, especially for discretionary leisure travel.

Moreover, decarbonization is not evenly distributed. Low-cost carriers with thinner customer margins and fewer business-class subsidies will face tougher choices. Ryanair has already warned that EU climate policies will raise average fares by €10 to €15 over the decade, and that’s with very low percentages of SAF. These aren’t abstract numbers. They will alter behavior. Short-haul trips under 1,000 kilometers may begin to shift to rail in Europe and East Asia, where infrastructure allows. Long-haul tourism may plateau as cost pressures mount. Business travel—already declining in relative terms since the pandemic—is unlikely to resume its former dominance, especially as virtual meetings and sustainability reporting norms take deeper hold.

As SAF mandates tighten, airlines will look for relief valves. Government subsidies, such as the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act’s $1.25–$1.75 per gallon tax credit for SAF, provide temporary cushioning, but that’s also not something that is guaranteed to persist given the current Administration’s wrecking ball approach. Those incentives phase out within the decade in any event, and few governments are eager to fund unlimited fuel subsidies for an industry still perceived as a luxury emitter. Some airlines are lobbying for contracts-for-difference or other hedge instruments to reduce price volatility. But even with policy support, costs will not return to fossil-era baselines.

One consequence will be fleet innovation. As SAF costs climb, the incentive to use less liquid fuel grows. Turboprop aircraft for short-haul regional routes are already 30–40% more fuel-efficient per passenger-kilometer than regional jets. Battery-electric and hybrid-electric turboprops are under development by firms like Heart Aerospace, Ampaire, and others, with 19 to 100 seat configurations and ranges from 200 to 1,000 kilometers. These aircraft avoid most SAF costs altogether. By 2035, they are likely to be competitive for short regional hops, especially in jurisdictions with high carbon prices or SAF mandates. Airports may also adjust, shifting infrastructure investments toward regional mobility rather than long-haul expansions.

As I’ve noted, our biological waste streams are immense, with 2.5 billion tons of food waste annually alone, and more from agricultural, animal husbandry and forestry. I’ve assessed virtually all of the feedstocks and processing technologies and am comfortable that there is zero conflict between climate goals, feeding people and biofuel use for longer haul aviation and shipping. Further, shifting those waste streams into biofuels is an inherent climate benefit because a lot of them decompose anaerobically into methane, leading to big climate challenges. That points to bioSAF as the dominant pathway, not because it’s perfect, but because it’s available, certifiable, and cheaper than synthetic options. Green hydrogen-derived e-kerosene remains and will remain prohibitively expensive and power-intensive. Blue hydrogen, produced from fossil methane with carbon capture, being used for synthetic fuels will likely never reach the economic, regulatory or public acceptance thresholds needed for mass adoption in aviation.

We are seeing the start of the repricing of the sky. SAF is not a footnote—it is the future of aviation fuel, and it’s not and will not be cheap. Every surcharge and fare increase is a signal. As SAF blends rise from 1% today to 10% and eventually 20% by 2035, ticket prices will climb. Some travelers will fly less. Some routes will shrink. Short-haul aviation will start shifting to electric propulsion. The net result isn’t the end of flying, but a subtle inversion of the curve: fewer people flying more carefully, on planes that burn fewer liquids and more electrons, with costs and choices reshaped by carbon. The sooner we acknowledge this trajectory, the better we can navigate it.

Whether you have solar power or not, please complete our latest solar power survey.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy